Community Embraces New Word Game at Mid-Year Play Day This past Sunday, families at Takoma Park’s Seventh Annual Mid-Year Play Day had the opportunity to experience OtherWordly for the first time. Our educational language game drew curious children and parents to our table throughout the afternoon. Words in Space Several children gathered around our iPads […]

Read more The growing field of digital humanities is hampered by a lack of motivation to share tools, and a lack of direct rewards from the academic establishment, says a new study published last month in the Digital Humanities Quarterly.

The growing field of digital humanities is hampered by a lack of motivation to share tools, and a lack of direct rewards from the academic establishment, says a new study published last month in the Digital Humanities Quarterly.

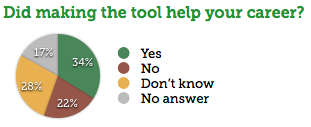

Digital humanities uses computers as part of research in arts and humanities. Computers are useless in isolation; they need software written to do interesting analyses. Some processing can be done using simple text processing tools to sort and count words. More complex research requires new tools (new computer programs) to be created. The study looked at the people who create those new tools. One key finding was that creating new software does little to help researcher’s careers.

The study examines responses from 54 individuals who work in the field. The survey was conducted in Spring 2008. The report was coauthored by Susan Schreibman, director of the Digital Humanities Observatory in Dublin, Ireland, and Ann Hanlon, the digital projects librarian at Marquette University.

The report says that while nearly all respondents consider their work on making tools to be a scholarly activity, “the range of responses to this question made it clear that many departments and institutions do not.” For the 2/3 of developers who don’t report career benefits, the authors note, “many respondents indicated that tool development led to more traditional scholarly outputs: conference papers and articles in journals (both peer-reviewed and non peer-reviewed). If the tool development itself was not rewarded, then these secondary products were.” The digital humanities field has “considerable work to do in making tool development an activity that is rewarded on par with more traditional scholarly outputs: articles, monographs, and conference presentations.”

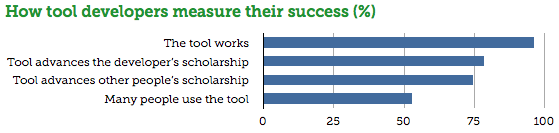

Without institutional support, developers look inward. This graph shows how developers measure their success:

The authors say the survey is representative, “Many of the tools developed by practitioners in the digital humanities community are represented in the survey. These include tools with ‘brand’ names many might recognize: Hyperpo, Image Markup Tool, Ivanhoe, Collex, Justa, nora, Monk, Tact, TactWeb, Tamarind, Tapor, Taporware, teiPublisher, TokenX, Versioning Machine, and Zotero.”

The report says that “tool developers, by and large, derived both personal satisfaction and professional recognition from their work. Sometimes this recognition translated into academic rewards such as promotion and tenure. But more frequently respondents wrote about the intellectual insights derived from their work, the new methodologies developed, deeper insights into their area of study and developing new models, and analytical methods.”

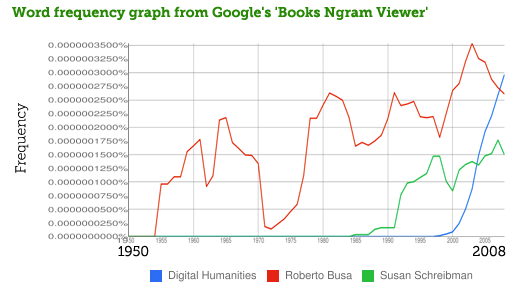

Digital humanities is a new twist on a centuries-old profession. Roberto Busa, a founder in digital humanities, wrote in 2008 (in a book co-edited by Schreibman), “Humanities computing is precisely the automation of every possible analysis of human expression (therefore it exquisitely a “humanistic” activity), in the widest sense of the word, from music to theater, from design and painting to phonetics, but whose nucleus remains the discourse of written texts.” Father Busa is an Italian Jesuit priest and early pioneer in the usage of computers for linguistic and literary analysis.

The authors conclude:

Meanwhile, other forms of digital humanities tools are being created by major software companies. In December 2010, Google released the ‘Books Ngram Viewer‘ for charting a timeline with the frequency of occurrence of various words. Here’s a chart of the frequency of the phrases “Digital Humanities,” “Roberto Busa,” and “Susan Schreibman” from 1950 to 2008 in books that Google has indexed:

Want more cool graphs? Here’s “10 Fascinating Word Graphs, From 200 Years of Google Books” in a blog post by Marshall Kirkpatrick at ReadWriteWeb.