Community Embraces New Word Game at Mid-Year Play Day This past Sunday, families at Takoma Park’s Seventh Annual Mid-Year Play Day had the opportunity to experience OtherWordly for the first time. Our educational language game drew curious children and parents to our table throughout the afternoon. Words in Space Several children gathered around our iPads […]

Read more A Hopi doll with painted headdress springs to life, spinning under my finger tips on a new iPad app from the University of Virginia Art Museum (UVaM).

A Hopi doll with painted headdress springs to life, spinning under my finger tips on a new iPad app from the University of Virginia Art Museum (UVaM).

The delightful app presents 19 different objects in 3D, to spin and zoom, providing an immediacy that rivals seeing an object in real life. In fact, it’s better in many ways than peering at an object through a protective case because the objects can be spun through a full 360°, view under bright lighting, at high resolution.

Personal exploration

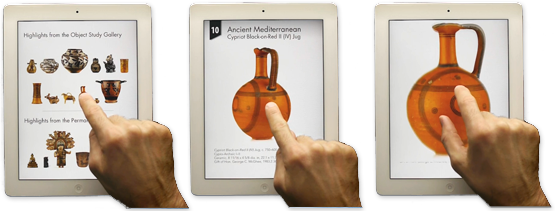

The free app presents the mobile visitor with a grid of objects (below, left):

Tapping any object brings up a spinnable 3D detailed view (above middle). The visitor can spin the object with their fingertip, or pinch to zoom in. Dragging up displays more of the caption, and tapping the corners or the bottom selects other objects.

A brilliant feature (above right) is a display of wax seal from the rear side of a 17th century Milanese painting. Wax seals are hard to make out clearly, but the app allows the user to drag the light source. Moving the light reveals the contours of the wax seal in a way that would otherwise be impossible. The visitor can see a two-headed eagle clutching a sword in one talon, and a royal orb in the other.

A brilliant feature (above right) is a display of wax seal from the rear side of a 17th century Milanese painting. Wax seals are hard to make out clearly, but the app allows the user to drag the light source. Moving the light reveals the contours of the wax seal in a way that would otherwise be impossible. The visitor can see a two-headed eagle clutching a sword in one talon, and a royal orb in the other.

For more of a flavor of the app, watch the following 1:45 minute demo from the museum:

“Our hope is that this app provides a level of access and interaction that isn’t always available to the public,” says Nicole Anastasi, Assistant Registrar at UVaM who spearheaded the project.

Escape from behind glass

Anastasi says that museum staff have the “luxury” of handling objects and inspecting them closely from all angles, but visitors can only peer through glass enclosed storage (case at right).

“The iPad offers a degree of access that we’ve never before been able to extend to our audience. Rather than inspecting static images, virtual visitors are now able to “touch” the art and interact with it on a more personal level. By downloading the UVAM app, iPad users are able to take our collection home with them.”

The app clearly fulfills it’s promise from museum director Bruce Boucher to “give users better access to the objects than simple, static photography, and will enabled details to be appreciated in a way that would challenge the naked eye.” The team did a good job, and the app has been well received. In the last two weeks since launch, it has 5 out of 5 stars in the U.S. app store, and enthusiastic reviews — a real accomplishment since most museum tour apps have been disappointing users.

How they did it

The app emerged out of discussions between Anastasi and two computer science professors at the university (Abhi Shelat and Jason Lawrence). The computer science professors were in the early stages of launching an app development company, Arqball. “We felt that interactive 3D graphics would help create amazing new educational materials,” says Shelat.

The app emerged out of discussions between Anastasi and two computer science professors at the university (Abhi Shelat and Jason Lawrence). The computer science professors were in the early stages of launching an app development company, Arqball. “We felt that interactive 3D graphics would help create amazing new educational materials,” says Shelat.

The app was funded internally by the university for an undisclosed budget, and took half a year from idea to completion. The app is free because “as a state institution, we are not allowed to make a profit on such things,” says Boucher. “In addition, we don’t want to limit our audience by naming a price–everyone should have access to the arts without worrying about fees,” adds Anastasi.

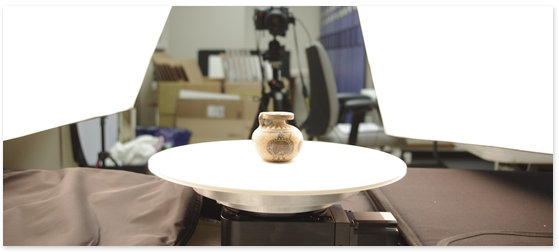

Arqball developed a photography rig with a stage, camera and lighting that were all computer-controlled. They capture images of the piece, rotating it a few degrees between shots, and then process the stream of images into a format that can be displayed within the app. Below, the team is photographing a Greek Aryballos, c 600-575 BCE. The Aryballos (flask) is on a white turntable, flanked by two light boxes, and the camera between.

Spinning an object on screen is effective, Shelat explains, because “people are very good at reading depth cues from motion. So a rotating model like ours lets then subconsciously develop their own ‘3D’ model of the piece.”

Other kinds of 3D

The concept of spinning 3D (virtual reality) has been used on the web for years, but it’s surprisingly more intuitive with a fingertip on a tablet than dragging a mouse. Also, an app can contain high-resolution images that would be impractical to display in realtime on the web. UVaM’s app is the first of its kind from a cultural heritage museum.

In the sciences, TouchPress has created a series of well-recieved apps. Shown below are iPad screens from TouchPress’ eBooks about the chemical element gold (left), gold jewelry (middle), and the planet Jupiter (right). Many of the images are fully-rotatable and pinch-zoomable, as in the UVaM app.

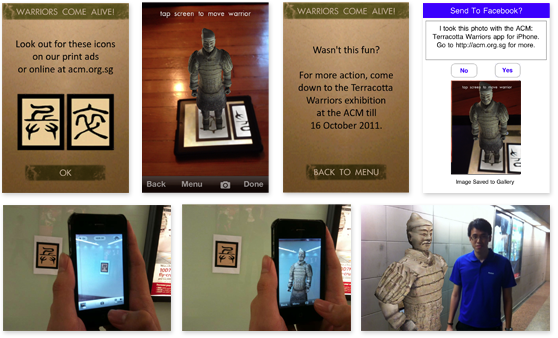

Another kind of 3D has recently emerged on handheld devices, using “augmented reality” apps to superimpose 3D into a video of a real scene. A recent app (below) from the Asian Civilisations Museum of Singapore used augmented reality to advertise their summer 2011 Terracotta Warriors exhibition.

The museum promoted the exhibition via publicity flyers, newspaper advertisements, and a display at the Dhoby Ghaut MRT train station, with instructions for commuters to download the free app, and aim their camera at a specially-constructed symbol. Above are four screens from the app. At the train station, a commuter can download the app, point the phone at the symbol. The app translates the symbol into the statue, which can appear alongside real life. Instead of manipulating the 3D using a fingertip, the user tilts and turns the camera, and the statue appears to be standing beside the symbol. The app has 4.5/5 star ratings in the Singapore App Store.

The museum promoted the exhibition via publicity flyers, newspaper advertisements, and a display at the Dhoby Ghaut MRT train station, with instructions for commuters to download the free app, and aim their camera at a specially-constructed symbol. Above are four screens from the app. At the train station, a commuter can download the app, point the phone at the symbol. The app translates the symbol into the statue, which can appear alongside real life. Instead of manipulating the 3D using a fingertip, the user tilts and turns the camera, and the statue appears to be standing beside the symbol. The app has 4.5/5 star ratings in the Singapore App Store.

A downside of augmented reality (vs. 3D images like the UVaM app) is that it is designed using realtime video game graphics, not real photography, so the visitors can not critically study the object in detail.

Future directions

Cultural heritage comes to life when the public is given access to the fascinating objects of the past, along with compelling backstories and context. But we can’t wait for publishers like TouchPress to expand their offerings. TouchPress is an interactive eBook publisher with high internal costs, and they need to partner with private collectors or traditional publishers to obtain their content. Their Solar System app cost approx $250,000 to produce, so unlike UVaM, they have to choose sensationalist topics presented at middle school to high school levels, to turn a profit.

We need more organizations like UVaM to create apps that present less common objects of cultural heritage, whether for the general public, or serious scholarship. Over time, as companies like Arqball hone their formula, the development costs will continue to fall, to be within reach of hundreds of museums.

The UVaM app is better than any other cultural heritage app on the market because it was designed to give the public a valuable experience that uses the capabilities of the device. It’s not merely replicating a paper brochure or audio tour.

If you are looking to connect the public with your collection, a great starting point would be to emulate the UVaM app. Building on their approach, you could improve on the model in a few ways:

Start with an optional, simple, pictorial help screen (example at right), not a letter from the museum director, nor a help video.

Start with an optional, simple, pictorial help screen (example at right), not a letter from the museum director, nor a help video.- Include more objects, including unique visualizations like the wax seal, or microscopic or X-Ray views. (Using Arqball’s approach, an object takes approximately 20 MB for a high res set of 3D images, so a maximum app size of 2GB corresponds to 100 high res objects.)

- Adapt for the smaller screens of the iPhone or iPod Touch. (UVaM is planning this.)

- Make the captions more interesting (perhaps with a lay-person’s version, and a more academic caption for deeper information). Irrelevant information like accession numbers and copyright reminders can minimized.

- Add a toolbar and use obvious-looking icons.

- Provide adjustable font sizes. This is vital for visually-disabled visitors.

- Get social. Apps should not be closed silos, rather they should allow easy sharing of still images or text by email, Tumblr, Twitter, etc., or saving images to the device’s library or DropBox.

Collaborate with cultural heritage scientists (who will probably share their content for free). Including some science broadens the appeal of the objects to a wider audience, and enriches visitor’s understanding. See some of the ways of examining artworks at WebExhibits.

Collaborate with cultural heritage scientists (who will probably share their content for free). Including some science broadens the appeal of the objects to a wider audience, and enriches visitor’s understanding. See some of the ways of examining artworks at WebExhibits.- Link your data. Pool together content with other institutions — let’s have thousands of interactive cultural objects by 2015!

Want to make your own 3D app?

“The iPad provides a fantastic platform to showcase the arts. As advances in technology change the way we view and research the arts, its critical to stay current and to be as innovative as possible,” says Anastasi. “Our intent is to expand the 3D collection to hundreds of objects.”

Arqball wants to develop more educational materials that use 3D technology. They have reusable software from the UVaM app, and Shelat says they are trying to drive down costs further “to make this technology available to all museums.” The cost for an app works out to $1-2k per object, for 10-20 objects, and there are economies of scale if there are a lot of objects. Museums can further cut costs if their staff can operate the photography rig themselves.

Source: View of the Dhoby Ghaut MRT station from the terracotta warrior app publisher, Magma Studio. Pictorial help from the Discover app.

4 comments on Put 3D objects at your visitors’ fingertips: UVaM on the iPad

Comments are closed.

29 Nov 2011, 11:27 am

Very nice article! I agree with your comprehensive overview of the area and think your suggestions for future directions are also quite good.

30 Nov 2011, 12:26 pm

Tablets are now in every hand and bring world to that screen. Nice application but I want to see Android version of this. Why only for iPad :(

12 Sep 2012, 12:38 am

It never ceases to amaze me how crisp graphics are these days. Sometimes it seems like they used some 3d scanning software to upload realistic images of everyday objects.

15 Apr 2013, 12:08 am

Thanks