Community Embraces New Word Game at Mid-Year Play Day This past Sunday, families at Takoma Park’s Seventh Annual Mid-Year Play Day had the opportunity to experience OtherWordly for the first time. Our educational language game drew curious children and parents to our table throughout the afternoon. Words in Space Several children gathered around our iPads […]

Read more Crowdsourcing can build virtual community, engage the public, and build large knowledge databases about science and culture. But what does it take, and how fast can you grow?

Crowdsourcing can build virtual community, engage the public, and build large knowledge databases about science and culture. But what does it take, and how fast can you grow?

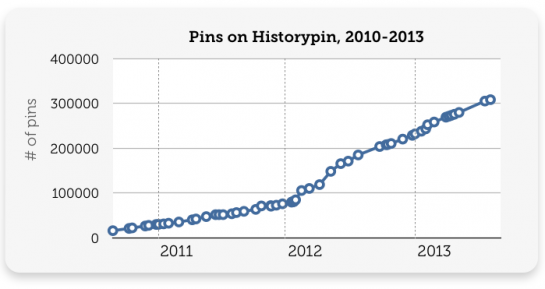

For some insight, we look at a crowdsourced history site: Historypin is an appealing database of historical photos, with dates, locations, captions, and other metadata. It’s called History “pin” because the photos are pinned on a map. (See recent article about Changes over time, in photos and maps.) Some locations have photos from multiple dates, showing how a place has changed over time, or cross-referenced with Google Maps StreetView. Currently, Historypin has 308k items, from 51k users, and 1.4k institutions. This is a graph of pins over the last three years:

For some insight, we look at a crowdsourced history site: Historypin is an appealing database of historical photos, with dates, locations, captions, and other metadata. It’s called History “pin” because the photos are pinned on a map. (See recent article about Changes over time, in photos and maps.) Some locations have photos from multiple dates, showing how a place has changed over time, or cross-referenced with Google Maps StreetView. Currently, Historypin has 308k items, from 51k users, and 1.4k institutions. This is a graph of pins over the last three years:

Aside from a change in their growth rate in early 2012, growth is linear. Since new users are always being added, the linear rate of content growth means users are losing interest. The following are activity rates:

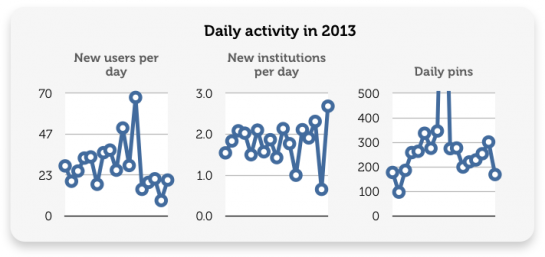

These graphs show some trends:

- New users: In early 2013, Historypin was pulling in around 23 new users a day, and that rate nearly doubled by late summer. But there was a precipitous fall in July 2013, and Historypin currently averages 17 new users per day.

- New institutions: This rate is more consistent, hovering around two new institutions per day. This rate will eventually limit as they saturate the market.

- Daily pins: Between personal and institutional users, and ignoring a one-time spike in May 2013, the rate of new contributions hovers around 200-300 items per day.

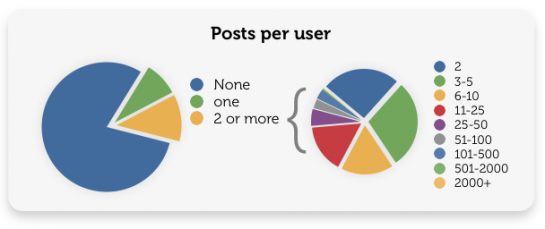

How much do users participate? Users can join for many reasons; e.g., to contribute, to be able to make favorites (bookmarks), of curiosity, or because they are spammers. As with many sites, most users are dormant, with just a few users doing most of the activity. The following are the number of pins posted per user:

Four out of five users never post a photo, and 9% only upload one image. The remaining 12% are enumerated in the above-right graph (starting at the top clockwise).

Not another drop in the bucket

It can be thankless to contribute to a crowdsourcing site, so successful projects provide a broader context and community. Historypin illustrates some good practices.

One strategy is to have themes. Rather than generic task (“do stuff”), a theme narrows the scope (“do stuff about the San Francisco Bay”). For example, here are three current Historypin themes:

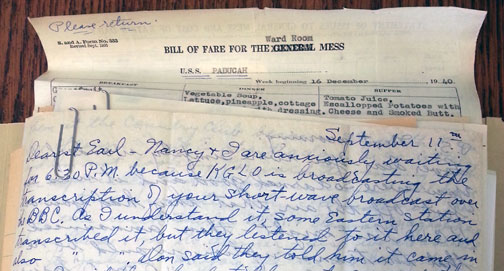

Themes are also used by the DIY History site from University of Iowa Libraries, where volunteers have been recruited to transcribe 37,507 handwritten pages of stories of Civil War soldiers and their families, of Iowa women making lives for themselves and their communities, and other themes like cookbooks, women’s lives, and the machinations of railroad barons. In DIY history, they have a large archive collection, organized into these themes.

Themes are also used by the DIY History site from University of Iowa Libraries, where volunteers have been recruited to transcribe 37,507 handwritten pages of stories of Civil War soldiers and their families, of Iowa women making lives for themselves and their communities, and other themes like cookbooks, women’s lives, and the machinations of railroad barons. In DIY history, they have a large archive collection, organized into these themes.

Here’s one of their letters, which needs transcription:

Narrow themes create a manageable and achievable workload, offsetting the drudgery of transcription, and providing satisfaction to volunteers.

Other good features

Projects must have robust, easy to use technology so that volunteers can easily get started and participate.

Projects must have robust, easy to use technology so that volunteers can easily get started and participate.

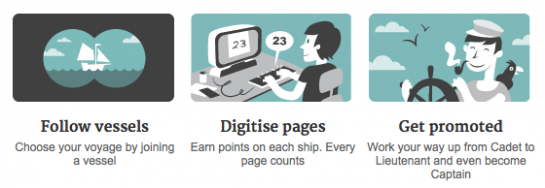

Also, draw on gamefication principles: Keep it fun and satisfying, include some challenge and sense of accomplishments. Old Weather has a clear process. It’s clear how to get involved, and easy to follow individual and project progress.

Another motivator for contributors is to have tangible outcomes or context. For example, Old Weather has tangible outcomes, providing Arctic and worldwide weather observations which are fed into climate models of past environmental conditions; and tracking past ship movements so historians can tell the stories of the people on board.

Appeal and ease of use matters. A similar idea, “Papers of the War Department” from the Center for History and New Media at George Mason University is progressing much slower, with 1.6k registered users (since June 2010), and approximately 200 people volunteering on the site per three month period. Volunteers have transcribed approx 4 thousand (out of 43k total) documents. At this rate, the Mason project will be done in 30 years. Check out their site, and you’ll see how it falls flat.

Appeal and ease of use matters. A similar idea, “Papers of the War Department” from the Center for History and New Media at George Mason University is progressing much slower, with 1.6k registered users (since June 2010), and approximately 200 people volunteering on the site per three month period. Volunteers have transcribed approx 4 thousand (out of 43k total) documents. At this rate, the Mason project will be done in 30 years. Check out their site, and you’ll see how it falls flat.

So what’s happening with Historypin?

Historypin is not growing exponentially. It’s not viral. Rather, Historypin’s rates of new users, new content, and new content per user have been falling in 2013. Here are a few theories:

Historypin is not growing exponentially. It’s not viral. Rather, Historypin’s rates of new users, new content, and new content per user have been falling in 2013. Here are a few theories:

- Failure to tap a nerve – Not many people care to help stick photo pins on a map, despite their themed projects. Some ideas don’t stick.

- Hasn’t reached a critical density – The earth has 149 million square kilometers of land. London is 1.5k square kilometers. A density of 1 photo per square kilometer would be require ~500x more pins.

- Monolingual – Historypin wants to have a global community, but the site is exclusively English. It’s not hard to translate a user interface. (See our 2012 article about outsourcing translations.)

- Closed system – There’s no way to export your content, link it to another system, nor is there an API. Similarly, they did not pursue a way for institutions to use their site on the backend, e.g., for a historical society in a small town to create a local site on their platform.

Questionable owner & future – The absence of clear funding sources undermines confidence in the long term prospects. Historypin was created by We Are What We Do, a “not-for-profit behaviour change company.” Their other projects range from branding a series of plastic shopping bags for a British retailer, to embroidered napkins with Tweets. The sole mention of a funding source for Historypin is a vague comment about support from Google.

Questionable owner & future – The absence of clear funding sources undermines confidence in the long term prospects. Historypin was created by We Are What We Do, a “not-for-profit behaviour change company.” Their other projects range from branding a series of plastic shopping bags for a British retailer, to embroidered napkins with Tweets. The sole mention of a funding source for Historypin is a vague comment about support from Google.- Bugs – Most of the technology on the Historypin site is slick and polished, but the core action of browsing photos on a map is buggy and awkward unless you zoom in close. Their mobile app is criticized by many users for being buggy and inadequate.

It’s a shame, because they are doing lots of things right, with a visually appealing site, an active and authentic blog, smooth technology, a mobile app, and some social media (Twitter, Facebook) to give contributors a sense of what’s new. In August 2013, Historypin acquired a smaller, similar project, LookBackMaps, but that has not boosted activity.

Invaluable labor

These considerations are important because crowdsourcing with volunteers has strong potential to deliver two kinds of content:

(a) Content which requires human judgement. For example, transcription projects focus on documents which are impossible to digitize automatically with OCR, but cost prohibitive to be transcribed by paid staff. Volunteers to the rescue! Once digitized, the documents become more vital, searchable in full text, read online, cross-referenced and mined by researchers. Fascinating insights can be extracted from large amounts of historical text.

(b) Content in which volunteers have unique knowledge. For example, the beauty of Historypin is that so much of the world’s photographic history is owned by individuals. When people share these old photos, scanning their family albums and the like, many other, interesting questions can be asked and explored.

What do you think?

What other crowdsourced projects in science and culture should folks know about? And what do you think are key ingredients for success?

Data source: Statistics from the home page and site of HistoryPin and other projects, over time.

18 Dec 2013, 7:04 am

[…] Eine Analyse der Social Media Plattform HistoryPin untersucht die Herausforderungen von Crowdsourcing-Projekten. idea.org […]