Community Embraces New Word Game at Mid-Year Play Day This past Sunday, families at Takoma Park’s Seventh Annual Mid-Year Play Day had the opportunity to experience OtherWordly for the first time. Our educational language game drew curious children and parents to our table throughout the afternoon. Words in Space Several children gathered around our iPads […]

Read moreReducing multidimensional data enables visitors to control what they see.

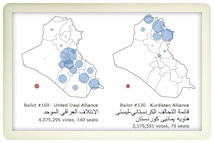

Data can be more understandable if users can choose how they navigate. In this case, vote counts from the 2005 Iraqi election can be tabulated different ways.

|

Problem

You need to display multiple dimensions of data, such as a city map, onto which you want to show the roads, the subway system, crime rates, and demographics.

Solution

Reduce the amount of data shown to the visitor by offering different views through the use of two methods:

- Predefined views: Provide a series of buttons on the edge of the city map. The visitor can choose a predefined view, such as all the roads, or just the parks.

- Choose your view: Break down the data into simpler categories, such as streets, highways, demographics, and housing density. The user can toggle these categories on and off, to compare what interests them.

Discussion

This technique reduces multidimensional data by allowing the visitor to choose only the dimensions of interest. Dynamic queries let the user change his or her view in real time.

The origins of these ideas can be traced to a technique called “worlds within worlds,” which displays a visual structure of multidimensional data by overloading different axes and by placing each coordinate system within another. Another technique called “parallel coordinates” explored the notion of choosing subsets of data (rather than subsets of dimensions) and using the parallel placement of axes in 2D. For example, an interactive graph could simultaneously show the amounts of vitamins in different foods, and the visitor could dynamically choose different subsets of foods. This would immediately convey, for example, how both leafy greens and milk are high in calcium; but that both milk and eggs are high in protein.