Community Embraces New Word Game at Mid-Year Play Day This past Sunday, families at Takoma Park’s Seventh Annual Mid-Year Play Day had the opportunity to experience OtherWordly for the first time. Our educational language game drew curious children and parents to our table throughout the afternoon. Words in Space Several children gathered around our iPads […]

Read more Metadata is a the glue that makes information useful. It is data about data. It could be a title, location, and camera settings for a photo; the history of a painting; the materials in a museum object; the authors of a journal article; or the time, date, and location of photo of a butterfly for a citizen science project. “Tags” added to blog posts, photos, or tweets are all a form of metadata, allowing others to quickly hone in on related items.

Metadata is a the glue that makes information useful. It is data about data. It could be a title, location, and camera settings for a photo; the history of a painting; the materials in a museum object; the authors of a journal article; or the time, date, and location of photo of a butterfly for a citizen science project. “Tags” added to blog posts, photos, or tweets are all a form of metadata, allowing others to quickly hone in on related items.

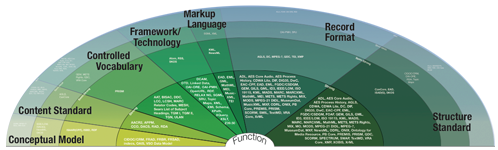

To make some sense of the sea of metadata, Jenn Riley mapped 105 metadata standards for cultural heritage.

A Tower of Babel

Standards are needed because metadata is only useful if we all use the same system. Imagine that you labeled your music collection with genres of “Classical” and “Hip Hop”, but your friend used the terms “Baroque” and “Rap.” You’d have trouble merging your collections.

A “taxonomy” defines terms, providing a common way to group things together. For example, the Linnaean taxonomy is a biological classification (taxonomy) set up by Carl Linnaeus, as set forth in his 1735 Systema Naturæ, with kingdoms, orders, families, genera. Nearly four centuries later, Linnaeus’ system is still generally in place for the Animal Kingdom, providing a common language for classifying the world’s animals. Many industries have unique, standardized taxonomies which are widely used.

“Search engines now have the incredible power to serve up millions of documents that contain words or phrases, and to do so almost instantaneously as users type. Taxonomy has a different power, the power to serve up a focussed selection of documents that best match the meaning of the ideas that users are searching for,” says Dave Clarke, CEO of Synaptica. “Search terminates with a set of results, but taxonomy never dead-ends; it constantly exposes alternative pathways and associated ideas.”

In the library field, taxonomies and metadata are a big deal, but “the sheer number of metadata standards in the cultural heritage sector is overwhelming, and their inter-relationships further complicate the situation,” says Jenn Riley, Metadata Librarian in the Indiana University Digital Library Program. Martyn Daniels, president of a publishing consultancy, notes that “we find ourselves drowning is a sea of acronyms and names. We are familiar with some we have no clue about others.” To shed some light, working with designer Devin Becker in 2010, Riley created a map of the 105 most heavily used or publicized metadata standards. [Her diagram, a PDF, is summarized below.]

In the library field, taxonomies and metadata are a big deal, but “the sheer number of metadata standards in the cultural heritage sector is overwhelming, and their inter-relationships further complicate the situation,” says Jenn Riley, Metadata Librarian in the Indiana University Digital Library Program. Martyn Daniels, president of a publishing consultancy, notes that “we find ourselves drowning is a sea of acronyms and names. We are familiar with some we have no clue about others.” To shed some light, working with designer Devin Becker in 2010, Riley created a map of the 105 most heavily used or publicized metadata standards. [Her diagram, a PDF, is summarized below.]

Map of metadata

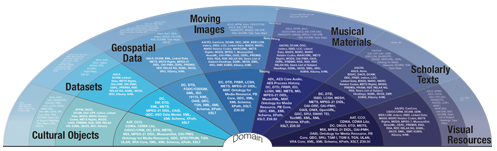

Here’s an overview of the standards that Riley maps, with four ways to group the standards, by: domain, community, function or purpose. This is a useful starting point for finding a standard for your own taxonomy, or for thinking about how to classify your data.

Domains

The domain is the type of material the standard used for.

- Cultural Objects are works of art, architecture, and other creative endeavor.

- Datasets are collections of primary data, typically before they are interpreted. They may be collected by scientific instruments, or by researchers in the sciences, social sciences, humanities, or other disciplines.

- Geospatial Data is information about the geographic location, either as the data about geographic places themselves or the relationship of a resource to a specific location.

- Moving Images are resources expressed as film, video, or digital moving images.

- Musical Materials express music in any form, including as audio, notation, and moving image.

- Scholarly Texts are produced as part of a research or scholastic process, and include both book-length and article-length material.

- Visual Resources are materials presented in fixed visual form, and can be either artistic or documentary in nature.

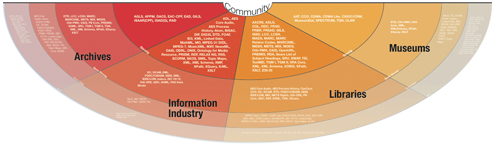

Community

The community is the groups that currently or potentially use the standard.

- Libraries collect and preserve both primary and secondary material in support of research, scholarship, teaching, and leisure. Can include academic, public, special, and corporate libraries.

- Archives are organizations that collect and preserve the natural outputs of the daily work of individuals and other organizational entities, including traditional records management processes. Their emphasis is frequently on the context of the creation of the materials and their relationship to one another.

- Museums collect and preserve artifacts from a given field with an emphasis on their curation and interpretation. Can include art, science, natural history, and many other types of museums.

- Information Industry are diverse organizations that make up both the public and the commercial Web. Can include technologies that support inventory and knowledge management, e-commerce, and the workings of the Internet.

Function

The function is the role a standard plays in the creation and storage of metadata. Some functions define the basic entities to be described, others define specific fields, others give guidance on how to record a specific data element, and still others define concrete data structures for the storage of information.

- Conceptual Models provide a high-level approach to resource description in a certain domain. They typically define the entities of description and their relationship to one another.

- Content Standards guide the creation of data for certain fields or metadata elements, sometimes defining what the source of a given data element should be.

- Controlled Vocabularies are enumerated (either fully or by stated patterns) lists of allowable values for elements for a specific use or domain. Includes classification schemes that use codes for values — such as the Dewey Decimal System.

- Framework/Technology encompasses models and protocols for the encoding and/or transmission of information, regardless of its specific format.

- Markup Languages feature specific aspects of a resource, typically in XML. They are unlike other “metadata” formats in that they provide not a surrogate for or other representation of a resource, but rather an enhanced version of the full resource itself.

- Record Formats are specific encodings for a set of data elements. Many structure standards are defined together with a record format that implements them.

- Structure Standards define, at a conceptual level, the data elements applicable for a certain purpose or for a certain type of material. These may be defined anew or borrowed from other standards. This category includes formal data dictionaries.

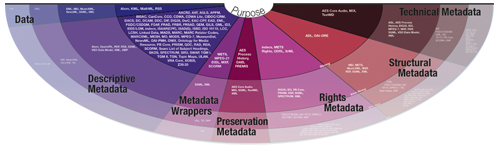

Purpose

The purpose is the general type of metadata the standard is designed to record.

- Data are standards whose purpose is to enclose the resource itself, possibly together with metadata or with added value such as markup.

- Descriptive Metadata standards include information to facilitate the discovery (via search or browse) of resources, or provide contextual information useful in the understanding or interpretation of a resource.

- Metadata Wrappers package together metadata of different forms, or metadata together with the resource itself.

- Preservation Metadata is the information needed to preserve, keep readable, and keep useful a digital or physical resource over time. Technical metadata is one type of preservation metadata, but preservation metadata also includes information about actions taken on a resource over time and the actors who take these actions. — e.g., information about conservation of a painting.

- Rights Metadata is the information a human or machine needs to provide appropriate access to a resource, provide appropriate notification and compensation to rights holders, and to inform end users of any use restrictions that may exist.

- Structural Metadata makes connections between different versions of the same resource, makes connections between hierarchical parts of a resource, records necessary sequences of resources, and flags important points within a resource.

- Technical Metadata documents the digital and physical features of a resource necessary to use it and understand when it is necessary to migrate it to a new format.

Riley says she created the map to “assist planners with the selection and implementation of metadata standards.” It’s an awesome starting point, and the map places the standards in the pie slices, depending on their connection to a category. See the diagram PDF, where you can zoom in and see the 105 standards mapped on the pies, and see how standards are interrelated. Riley also made a glossary about each standard.

There are many other metadata standards for the sciences and industry.