Community Embraces New Word Game at Mid-Year Play Day This past Sunday, families at Takoma Park’s Seventh Annual Mid-Year Play Day had the opportunity to experience OtherWordly for the first time. Our educational language game drew curious children and parents to our table throughout the afternoon. Words in Space Several children gathered around our iPads […]

Read moreTag: access

Online courses with very large enrollments have rapidly matured in the last two years, led largely by experiments outside mainstream academia by Coursera, Udacity and edX. Ambitious educators, technologists, and funders have created courses on diverse topics, and over five million students worldwide have registered for classes. And 3% have completed the courses. What can we learn? (more…)

Online courses with very large enrollments have rapidly matured in the last two years, led largely by experiments outside mainstream academia by Coursera, Udacity and edX. Ambitious educators, technologists, and funders have created courses on diverse topics, and over five million students worldwide have registered for classes. And 3% have completed the courses. What can we learn? (more…)

Crowdsourcing means involving a lot of people in small pieces of a project. In educational and nonprofit outreach, crowdsourcing is a form of engagement, such as participating in an online course, collecting photos of butterflies for a citizen-science project, uploading old photos for a community history project, deciphering sentences from old scanned manuscripts, playing protein folding games to help scientists discover new ways to fight diseases, or participating in online discussions. (more…)

Crowdsourcing means involving a lot of people in small pieces of a project. In educational and nonprofit outreach, crowdsourcing is a form of engagement, such as participating in an online course, collecting photos of butterflies for a citizen-science project, uploading old photos for a community history project, deciphering sentences from old scanned manuscripts, playing protein folding games to help scientists discover new ways to fight diseases, or participating in online discussions. (more…)

Imploded by the same forces that have disrupted the broader publishing industry, the dictionary business struggles to get a grip on the online/mobile world. “Our research tells us that most people today get their reference information via their computer, tablet, or phone” said Stephen Bullon, Macmillan Education’s Publisher for Dictionaries, “and the message is clear and unambiguous: the future of the dictionary is digital.” (more…)

Imploded by the same forces that have disrupted the broader publishing industry, the dictionary business struggles to get a grip on the online/mobile world. “Our research tells us that most people today get their reference information via their computer, tablet, or phone” said Stephen Bullon, Macmillan Education’s Publisher for Dictionaries, “and the message is clear and unambiguous: the future of the dictionary is digital.” (more…)

![]() Search the pages of America’s historic newspapers (1836-1922) with the new Chronicling America web site from the Library of Congress. Chronicling America provides access to information about historic newspapers and select digitized newspaper pages. Here are 3 newspapers from 100 years ago today: (more…)

Search the pages of America’s historic newspapers (1836-1922) with the new Chronicling America web site from the Library of Congress. Chronicling America provides access to information about historic newspapers and select digitized newspaper pages. Here are 3 newspapers from 100 years ago today: (more…)

![]() Science journal subscriptions can cost libraries several thousand dollars a year, yet most institutions members only make use of a few articles from each of these journals. The huge subscription expenses limit how many journals each school or company can carry. Even single article pricing can be staggering, at $30-50 each. Sinisa Hrvatin, a doctoral candidate at Harvard, and his roommate Robert McGrath believe they have a better way. (more…)

Science journal subscriptions can cost libraries several thousand dollars a year, yet most institutions members only make use of a few articles from each of these journals. The huge subscription expenses limit how many journals each school or company can carry. Even single article pricing can be staggering, at $30-50 each. Sinisa Hrvatin, a doctoral candidate at Harvard, and his roommate Robert McGrath believe they have a better way. (more…)

Open textbooks are receiving a potential boost by an ambitious new, organized peer review project organized by the University of Minnesota. The average college student suffers with $1,000 or more in annual textbook costs; however, if more professors adopt open textbooks, higher education will become more affordable. (more…)

Open textbooks are receiving a potential boost by an ambitious new, organized peer review project organized by the University of Minnesota. The average college student suffers with $1,000 or more in annual textbook costs; however, if more professors adopt open textbooks, higher education will become more affordable. (more…)

Over 30,000 objects are now available for anyone to savor and study online, for free, in impressive high resolution, in Google’s ‘Art Project.” This is 30x expansion from the thousand objects in the first version launched in February 2011. See our prior article, The virtual vs. the real: Giga-resolution in Google Art Project. The project now has 151 partners in 40 countries; in the U.S., the initial four museums has grown to 29 institutions, including the White House and some university art galleries.

Over 30,000 objects are now available for anyone to savor and study online, for free, in impressive high resolution, in Google’s ‘Art Project.” This is 30x expansion from the thousand objects in the first version launched in February 2011. See our prior article, The virtual vs. the real: Giga-resolution in Google Art Project. The project now has 151 partners in 40 countries; in the U.S., the initial four museums has grown to 29 institutions, including the White House and some university art galleries.

See the site: Google Art Project (more…)

“Being able to teach machine learning to tens of thousands of people is one of the most gratifying experiences I’ve ever had,” says Stanford University computer science professor Andrew Ng.

“Being able to teach machine learning to tens of thousands of people is one of the most gratifying experiences I’ve ever had,” says Stanford University computer science professor Andrew Ng.

Over 100,000 students signed up for his free, fall 2011 course on machine learning. The impacts were huge. Over 12% of the students completed the course, and received a statement of accomplishment. Ng says he “heard many stories from students about how they’re using it at work, about how it’s inspired them to go back to school, and so on.” In contrast, Ng’s normal, for-credit course at Stanford, one of the most popular on campus, would enroll 350 students.

It’s part of a new revolution in higher education, and it’s serious learning. They deliver complete courses where students are not only watching web-based lectures, but also actively participating, doing exercises, and deeply learning the material. Students are expected to devote ~12 hours a week to the course, to read and watch course materials, complete assignments, and take quizzes and an exam. ![]() Online students did not receive one-on-one interaction with professors, the full content of lectures, or a Stanford degree — those who completed the course received a statement of accomplishment. Course materials include prerecorded lectures (with in-video quizzes) and demos, multiple-choice quiz assignments, automatically-checked programming exercises with an interactive workbench, midterm and final exams, a discussion forum, optional additional exercises with solutions, and pointers to readings and resources.

Online students did not receive one-on-one interaction with professors, the full content of lectures, or a Stanford degree — those who completed the course received a statement of accomplishment. Course materials include prerecorded lectures (with in-video quizzes) and demos, multiple-choice quiz assignments, automatically-checked programming exercises with an interactive workbench, midterm and final exams, a discussion forum, optional additional exercises with solutions, and pointers to readings and resources.

Online courses can be a great way to teach (and learn) new skills. They can be small and highly personal, or scale to thousands of students. As followup to my post about “What is an online course?”, let’s look behind the scenes at a few kinds of successful online classes, rich with video, feedback and large amounts of real-world work.

Structuring a course

![]() The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) currently has six 8 or 10 week online courses. The cost is $200 for self-guided courses, or $350 for instructor-led. The latter enroll 30-45 students. MoMA offers both knowledge classes, e.g., “Modern and Contemporary Art: 1945–1989,” and knowledge/skill courses, e.g., “Materials and Techniques of Postwar Abstract Painting,” in which students do hands-on work at home.

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) currently has six 8 or 10 week online courses. The cost is $200 for self-guided courses, or $350 for instructor-led. The latter enroll 30-45 students. MoMA offers both knowledge classes, e.g., “Modern and Contemporary Art: 1945–1989,” and knowledge/skill courses, e.g., “Materials and Techniques of Postwar Abstract Painting,” in which students do hands-on work at home.

The instructor-led classes offer structure, socialization and personalization; whereas, the self-guided courses are about individual freedom, providing access to curated articles and video, with no live instructor facilitation nor social interaction with other students.

The studio-art offerings have weekly assignments. For example, students paint canvases using the materials and techniques of iconic artists. They photograph their works in progress and finished, and upload them to discuss with other students and the instructor. Wendy Woon directs MoMA’s education department. She feels the 10-week timeframe has worked well for studio art, allowing enough time for a sense of trust and community to develop in the discussion forums so that students are willing to have “critical conversations” criticizing each other’s work.

The studio-art offerings have weekly assignments. For example, students paint canvases using the materials and techniques of iconic artists. They photograph their works in progress and finished, and upload them to discuss with other students and the instructor. Wendy Woon directs MoMA’s education department. She feels the 10-week timeframe has worked well for studio art, allowing enough time for a sense of trust and community to develop in the discussion forums so that students are willing to have “critical conversations” criticizing each other’s work.

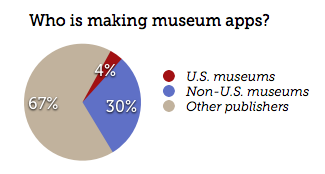

The vast majority of museums are totally ignoring mobile apps.

The vast majority of museums are totally ignoring mobile apps.